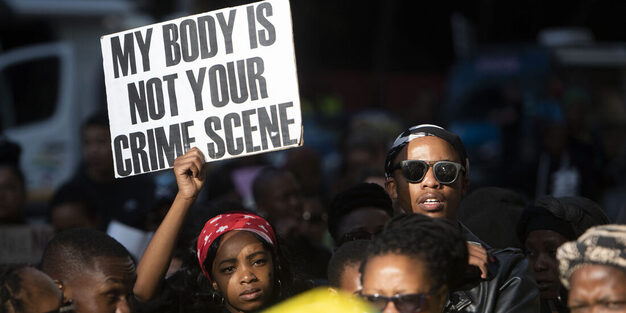

Gender Based Violence

Social Development Minister Lindiwe Zulu once said that the names of victims of gender-based violence in South Africa read like a casualty list of a war zone.

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a serious and widespread problem in South Africa, affecting nearly each and every aspect of life. GBV (which disproportionately impacts women and girls) is wide spread, and deeply entrenched in institutions, cultures and traditions in South Africa. Every day in the media we read of men abusing women or children. Abuse against women happens in all spheres of our society. The rate at which women in South Africa are murdered by intimate partners is five times higher than the global average, according to the World Health Organisation.

Exactly what is gender-based violence?

GBV happens as a result of normative role expectations and unequal power relationships between genders in a society.

There are lots of different definitions of GBV, however it can be largely described as the general term used to capture violence that occurs as a result of the normative role expectations associated with each gender, along with the unequal power relationships between genders, within the context of a specific society.” Bloom, Shelah S. 2008.

Patriarchy is a social system that treats men as superior to women – where women can not protect their bodies, satisfy their basic needs, engage fully in society and men perpetrate violence against women with impunity.

In 2012, a study performed by Gender Links found that 77% of women in Limpopo, 51% in Gauteng, 45% in the Western Cape and 36% in KwaZulu-Natal had suffered some form of GBV (Gender Links 2012). Men were the primary perpetrators of this violence. For instance, 76% of men in Gauteng, 48% in Limpopo and 41% in KwaZulu-Natal mentioned to perpetrating GBV (Gender Links 2012). A study surveying 1 306 women in three South African provinces revealed that 27% in the Eastern Cape, 28% in Mpumalanga and 19% in Limpopo had been physically abused in their life time by a current or ex-spouse (Abrahams et al. 1999). The exact same study examined the occurrence of emotional and financial abuse encountered by women in the year earlier to the study and discovered that 51% of women in the Eastern Cape, 50% in Mpumalanga and 40% in Limpopo were exposed to these kinds of abuse (Abrahams et al. 1999).

Culturally, men are usually placed in a powerful position in relation to females due to practices like as lobola, ukuthwala and Sharia law where females naturally hold a secondary position to males (Althaus 1997; Ansell 2001; Moosa 1996). This often turns out to be normalised, with both men and women being socialised into conforming to these cultural and religious practices. Regrettably, many of these practices implicitly or explicitly condone and tolerate GBV. Numerous scientific studies (e.g. Holt et al. 2008; Krug et al. 2015) have shown that violence is a learned behaviour for both males and females. These scientific studies claim that younger people who grow up in families characterised by violence are a lot more most likely to normalise violence in their relationships later in life. Nonetheless, it is not usually the case that children who notice parents fighting will automatically turn out to be violent. Occasionally there are mediating protective factors that result in these children not becoming violent or remaining in violent relationships. Nevertheless, many studies still establish this link.

Forms of gender-based violence

Domestic violence

Domestic violence is the most typical form of GBV amongst partners. It often comprises of physical violence or threats of violence. This kind of violence may also include sexual assault, battery, coercion and sexual harassment (Sigsworth 2009; Tshwaranang Legal Centre 2012).

Physical violence

This kind of GBV comprises of hitting, slapping, kicking, punching, pushing and so forth. Weapons such as knives and other sharp instruments are often used during the course of physical violence (Sigsworth 2009; Tshwaranang Legal Centre 2012).

Emotional violence

Emotional violence frequently comprises of verbal abuse, name calling and denigration of the other. It involves acts of embarrassment, humiliation and contempt. These acts impact one’s sense of self, self-esteem and selfconfidence (Ludsin & Vetten 2005).

Economic violence

This consists of control of a partner’s assets, access to money and other economic resources. The male partner may be unwilling for his female partner to work or may manage and abuse her payment for work done (Ludsin & Vetten 2005).

Sexual violence

This is the most frequent form of GBV and may include rape, sexual harassment, sexual exploitation and trafficking for sexual reasons (Mathews 2010; Vetten 2003).

Femicide

This is characterised by the killing of a female partner by an intimate male partner and is regarded to be the most extreme outcome of GBV (Mathews 2010; Vetten 2005).

The psychological consequences of GBV include:

The Domestic Violence Act in South Africa have the following provisions to protect victims of domestic violence:

This Act is very clear about things that need to take place to protect victims of domestic violence, but there are dilemmas with its execution. The role of the police In terms of the Act, the police need to play a role of helping the victim or arresting the perpetrator of GBV. The police are also required to enable the victim to seek legal assistance, particularly obtaining a protection order and serving it on the perpetrator. It is also crucial for the police to refer the victim for counselling or to a shelter for safety and accommodation. Although the Act is clear about the role of the police, studies have discovered that many police officers are reluctant to help victims of GBV as they see these cases as a ‘private matter between two partners/lovers’ (Mathews & Abrahams (2003].

Written by: Bertus Preller, a Family Law Attorney at Maurice Phillips Wisenberg.

Exactly what is gender-based violence?

GBV happens as a result of normative role expectations and unequal power relationships between genders in a society.

There are lots of different definitions of GBV, however it can be largely described as the general term used to capture violence that occurs as a result of the normative role expectations associated with each gender, along with the unequal power relationships between genders, within the context of a specific society.” Bloom, Shelah S. 2008.

Patriarchy is a social system that treats men as superior to women – where women can not protect their bodies, satisfy their basic needs, engage fully in society and men perpetrate violence against women with impunity.

In 2012, a study performed by Gender Links found that 77% of women in Limpopo, 51% in Gauteng, 45% in the Western Cape and 36% in KwaZulu-Natal had suffered some form of GBV (Gender Links 2012). Men were the primary perpetrators of this violence. For instance, 76% of men in Gauteng, 48% in Limpopo and 41% in KwaZulu-Natal mentioned to perpetrating GBV (Gender Links 2012). A study surveying 1 306 women in three South African provinces revealed that 27% in the Eastern Cape, 28% in Mpumalanga and 19% in Limpopo had been physically abused in their life time by a current or ex-spouse (Abrahams et al. 1999). The exact same study examined the occurrence of emotional and financial abuse encountered by women in the year earlier to the study and discovered that 51% of women in the Eastern Cape, 50% in Mpumalanga and 40% in Limpopo were exposed to these kinds of abuse (Abrahams et al. 1999).

Culturally, men are usually placed in a powerful position in relation to females due to practices like as lobola, ukuthwala and Sharia law where females naturally hold a secondary position to males (Althaus 1997; Ansell 2001; Moosa 1996). This often turns out to be normalised, with both men and women being socialised into conforming to these cultural and religious practices. Regrettably, many of these practices implicitly or explicitly condone and tolerate GBV. Numerous scientific studies (e.g. Holt et al. 2008; Krug et al. 2015) have shown that violence is a learned behaviour for both males and females. These scientific studies claim that younger people who grow up in families characterised by violence are a lot more most likely to normalise violence in their relationships later in life. Nonetheless, it is not usually the case that children who notice parents fighting will automatically turn out to be violent. Occasionally there are mediating protective factors that result in these children not becoming violent or remaining in violent relationships. Nevertheless, many studies still establish this link.

Forms of gender-based violence

Domestic violence

Domestic violence is the most typical form of GBV amongst partners. It often comprises of physical violence or threats of violence. This kind of violence may also include sexual assault, battery, coercion and sexual harassment (Sigsworth 2009; Tshwaranang Legal Centre 2012).

Physical violence

This kind of GBV comprises of hitting, slapping, kicking, punching, pushing and so forth. Weapons such as knives and other sharp instruments are often used during the course of physical violence (Sigsworth 2009; Tshwaranang Legal Centre 2012).

Emotional violence

Emotional violence frequently comprises of verbal abuse, name calling and denigration of the other. It involves acts of embarrassment, humiliation and contempt. These acts impact one’s sense of self, self-esteem and selfconfidence (Ludsin & Vetten 2005).

Economic violence

This consists of control of a partner’s assets, access to money and other economic resources. The male partner may be unwilling for his female partner to work or may manage and abuse her payment for work done (Ludsin & Vetten 2005).

Sexual violence

This is the most frequent form of GBV and may include rape, sexual harassment, sexual exploitation and trafficking for sexual reasons (Mathews 2010; Vetten 2003).

Femicide

This is characterised by the killing of a female partner by an intimate male partner and is regarded to be the most extreme outcome of GBV (Mathews 2010; Vetten 2005).

The psychological consequences of GBV include:

- posttraumatic anxiety disorder (including nightmares, intrusive memories, flashbacks, numbing, hyperarousal, hypervigilance);

- major depression (temper outbursts, tiredness, worthlessness, hopelessness, helplessness, irritability, insomnia, restlessness, loss of appetite or overeating);

- complicated trauma (persistent feelings of emptiness, anger, sadness, self-mutilation, preoccupation with the perpetrator);

- generalised anxiety conditions (overanxious, fearful, constantly worried).

The Domestic Violence Act in South Africa have the following provisions to protect victims of domestic violence:

- right to apply and receive protection order;

- the police officer has a duty to assist the victim of domestic violence;

- the police officer has a duty to arrest the perpetrator of domestic violence;

- the victim has a right to receive psychological and medical help.

This Act is very clear about things that need to take place to protect victims of domestic violence, but there are dilemmas with its execution. The role of the police In terms of the Act, the police need to play a role of helping the victim or arresting the perpetrator of GBV. The police are also required to enable the victim to seek legal assistance, particularly obtaining a protection order and serving it on the perpetrator. It is also crucial for the police to refer the victim for counselling or to a shelter for safety and accommodation. Although the Act is clear about the role of the police, studies have discovered that many police officers are reluctant to help victims of GBV as they see these cases as a ‘private matter between two partners/lovers’ (Mathews & Abrahams (2003].

Written by: Bertus Preller, a Family Law Attorney at Maurice Phillips Wisenberg.

Abused?How to get a protection order?

|

More on Gender Violence and Abuse

Financial Abuse |

Revenge Pornography |

Emotional Abuse |